In my philosophy of art course this term we are talking about Tolstoy and Collingwood on expression, Plotinus and Hume and Kant on beauty, and Dewey as a kind of semi-successful synthesis of these two dimensions of art (artist and audience, expression and beauty). As the course goes on we will spend more time discussing whether any of this sort of theorizing survives the new approaches of conceptual art. I think it does – at least, I think these ideas and thinkers remain useful for thinking about art today – but I don’t want to argue that here.

The word ‘beauty’ is a mess in philosophy, as perhaps befits the unbeautiful state of the broader human world. The important (meta-)property this word is trying to pick out in aesthetics is the one involved when you say “what a magnificent landscape” or “you must see that movie” or “Memoirs of Hadrian is a genuinely great work of literature” or even “Cezanne’s many landscapes with Mont Sainte-Victoire and still lives with apples gave us a new way of seeing the world, which has since become one of our basic cognitive touchstones for judging and understanding visual art.” (In this last it is the way of seeing offered in a variety of paintings offered as the property you must notice if you are also to perceive their beauty, along with the usual move indicating an expansion of our conceptual resources in understanding art on the basis of Cezanne’s success.) Plausibly, this property is something like a type of interest or enjoyment which is (1) valuable and/or normative and (2) in some way socially shared, intersubjective, general, or universal. (Credit here to Richard Warner and Steven Wagner as well as to Immanuel Kant for shaping my thinking on this subject.)

But for our purposes ‘beauty’ can be semi-defined as ‘the property(-ies) that make artworks interesting as artworks to their audiences’, sidestepping the harder questions. The point of the term theoretically speaking is to organize audience aesthetics, the reception of artworks by audiences.

The philosophical problem here, which at least has structural similarities to a real problem that artists face in relating to their audiences, is this. We have a reasonably good account of art from the artist’s point of view in the expression theories. And we can form a reasonably good working grasp of the sorts of value one may find in the experience of art first and foremost from the artworks themselves, second from the works of the best critics, and also from the best philosophers of aesthetic experience, such as Plato, Plotinus, Hume, Kant, and Nietzsche.

Presumably an adequate theory of art would provide a unified view of these two dimensions of art.

Collingwood and Dewey both had useful and somewhat similar things to say about how these two faces of art might be connected. For Collingwood, the making of an artwork is an act of imaginative emotional expression. The audience’s job is then to reconstruct that expressive act from the performance or object the act yielded, which means, in part, to use the performance or object as a vehicle for their own expression, or at least to try it out in imagination as a candidate for such. (Judgments like “very impressive, but not for me” can sometimes acknowledge artistic success along with the unwillingness of that audience member to inhabit the artist’s perspective, on this view.) For Dewey, the making of an artwork is an encoding of experiences, and although there are differences in the details, the overall picture of what the audience does is again a perceiving aimed at reenacting the artist’s expressive process, at least within the limits of one’s own different perspective.

Dewey’s word ‘experience’, and his idea that the artist must “embody in himself the attitude of the perceiver while he works” – meaning not that he must worry about what audiences or fellow artists will think, but that he is creating something for perception and should generally treat it as such as he makes it – help take something like Collingwood’s idea and connect it more explicitly to the idea of beauty. Perhaps ultimately beautiful expressions are just some subset of interesting ones, but one connects the idea of beauty to that of experiences and series of perceptions which are ‘textured,’ meaningfully directed sensual surfaces, seemingly disparate ideas unified at some level just beyond our ability to directly grasp, and which unify us in their apprehension.

This last (and crucial) social dimension of art is more or less left out of the current path of thought, rendering it incomplete, but with one more ingredient we will at least have the ingredients for a picture of the connection between the artist’s expression and the audience’s reception. This piece is the answer to Plato’s question about where art comes from – where artists get their inspirations.

Broadly speaking answers to this question fall into five categories, which should not be taken as mutually exclusive: the supernatural (God, muses, spirits); the intellectual (ideas or theories, theses about art itself); the natural (typically, sensuous forms which the artist’s power of selection singles out for attention owing to their distinctive power of aesthetic reward; ‘significant form’); the cultural (the artist as the vehicle of one or more identities which the artist inhabits and which are taken to have their own unique characters of expression; or, as the channeler of broader energies informing the time and place in which she lives); and the individual (the artist as spokesperson for her own viewpoint, or as idiot-savant of the genius of her own unconscious).

My proposal here is merely structural: that where there is art there is inspiration, and where there is inspiration there is some source or sources for it, drawn from any or all of the five categories above. Even if we think of expression in the older terms of feeling or emotion, feelings and emotions come out of people in their encounters with the world. The ‘source’ of art is just the complex combination of past experiences and reflections on those experiences to which the artist reacts and whose outlines form the space which her aesthetic idea indicates a path through and/or organizes. The art is not reducible to its source(s), but as an expression in reaction to them it is not independent from it either, and in reconstructing the expressive act that constitutes the work the audience must find connected sources in their own experience if they are to understand the work’s aesthetic idea and find meaning in it.

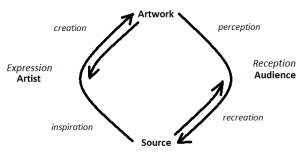

The following diagram is offered as a way to organize this particular way of looking at the relationship between artist, artwork, and audience:

The reversed half-arrows here are meant to indicate that as the artist moves from inspiration to creation, she enters into dialogue with her materials and with the finished work that she sees emerging from her creative process; and that as the audience member moves from perception to recreation, she attempts to connect the thing she is perceiving to the sources from which it came, and as taking a particular stance with respect to those sources, so that she can perceive it as the kind of expressive act it is.

On this view, then, the property formerly known as beauty is something like a positive feedback loop between the perception of the artwork and the recreation of the ‘source’, a meta-level property of audience reception. When what there is to see gives us a lot to think or feel, which makes us look again, which gives us more to think or feel, culminating in a kind of satisfaction which constitutes one kind of aesthetic understanding.